|

| |

Roman Time Keeping

Much of our current

terminology about time and time keeping originated during Roman times. Much of our current

terminology about time and time keeping originated during Roman times.

After the Julian reform of 46 B.C. the Roman calendar -like

ours, which is its offspring -was governed by the length of the earth’s circuit

of the sun. The twelve months of our year retain by the sequence, the length,

the names which were assigned them by the genius of Caesar and the prudence of

Augustus. From the beginning of the empire each of them, including February in

both ordinary years and leap year, contained the number of days to which we are

still accustomed.

Another element of Roman time

that is familiar to us is the the week. The week divided into seven

days, named after planets was borrowed from the Babylonians by way of the Jews.

The seven day week of late Roman times has survived in the Latinate names for

the days (except for Sunday, "the Lord's Day"). In English we substitute a

Germanic divinity's name for Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.

| English |

Sunday |

Monday |

Tuesday |

Wednesday |

Thursday |

Friday |

Saturday |

| French |

dimanche |

lundi |

mardi |

mercredi |

jeudi |

vendredi |

samedi |

| Italian |

Domenica |

Lunedi |

Martedi |

Mercoledi |

Giovedi |

Venerdi |

Sabato |

| Roman equivalent |

sun's

day |

luna's (Moon) day |

Mars' day |

Mercury's day |

Jupiter's day |

Venus' day |

Saturn's day |

The seven day week did not

become part of Roman life until late in their history (321 AD). Before this

time, the Romans had a division of the month based on a market day

recurring every eight days. The market day was called nundinae (novem dies =

"nine days," the Romans counted both ends of a series), but this unit of time

did not seem to shape the lives of the ancient Romans the way our week does for

ours with its regular recurring rest days at its end (Saturday and Sunday).

In addition to the old official division of the months by

the Calends (first of each month), the Nones (the fifth or seventh day) and the

Ides

(the thirteenth or fifteenth day), the division into weeks of seven days is subordinate

to the seven planets whose movements were believed to regulate the universe. By

the beginning of the third century this usage had become so firmly

anchored in the popular consciousness that Dio Cassius considered it

specifically Roman. With only one minor modification-the substitution of the day

of the Lord, for the day of the Sun, it has in most countries of Latin speech

survived both the decadence of the astrologers and the triumph of Christianity.

Finally each day of the seven was divided into twenty-four hours which were

reckoned to begin, not as with the Babylonians, at sunrise, nor, as among the

Greeks, at sunset, but as but as is still the case with us, at midnight. This

ends the analogies between time a the ancients counted it and as we do; the

Latin “hours,” late Intruders Into the Roman day, though they bear the same name

and were of the same number as ours, were in reality very different.

|

The

Greeks' Sun-Dials

Both word and thing were an invention of the Greeks deriving from the

process of mensuration. Toward the end of the fifth century B.C. they had

learned to observe the stages performed by the sun in its march across the

sky. The sun-dial of Meton which enabled the Greeks to register these,

consisted of a

concave hemisphere of stone, having a strictly horizontal brim, with a

pointed metal stylus rising in the centre. As soon as the sun entered the

hollow of the hemisphere, the shadow of the stylus traced in a reverse

direction the diurnal parallel of the sun. Four times a year, at the

equinoxes and the solstices, the shadow movements thus obtained were

marked by a line incised in the stone; and as the curve of the spring

equinox coincided with that of the autumn equinox, three concentric

circles were finally obtained, each of which was then divided into twelve

equal parts. All that was further needed was to join the corresponding

points on the three circles by twelve diverging lines to obtain the twelve

hours which punctuated the year's course of the sun as faithfully

recorded by the dial. Hence the dial derived its name "hour counter",

preserved in the Latin horologmm and in the French horloge. Following the

example of Athens, the other Hellenic cities coveted the honor of

possessing sun-dials, and their astronomers proved equal to the task of

applying the principle to the position of each. The apparent path of the

sun varied of course with the latitude of each place, and the length of

the shadow cast by the stylus It was consequently different in one city

and another. At Alexandria it was only three-fifths of the height of the

stylus, at Athens three-quarters; it was nearly nine-elevenths at Tarentum

and reached eight-ninths at Rome. As many different sun-dials had to be

constructed as there were different cities. The Romans were among the last

to appreciate the need. And just as they felt no need to count the hours

till two centuries after the Athenians, so they took another hundred years

to learn to do it accurately. consisted of a

concave hemisphere of stone, having a strictly horizontal brim, with a

pointed metal stylus rising in the centre. As soon as the sun entered the

hollow of the hemisphere, the shadow of the stylus traced in a reverse

direction the diurnal parallel of the sun. Four times a year, at the

equinoxes and the solstices, the shadow movements thus obtained were

marked by a line incised in the stone; and as the curve of the spring

equinox coincided with that of the autumn equinox, three concentric

circles were finally obtained, each of which was then divided into twelve

equal parts. All that was further needed was to join the corresponding

points on the three circles by twelve diverging lines to obtain the twelve

hours which punctuated the year's course of the sun as faithfully

recorded by the dial. Hence the dial derived its name "hour counter",

preserved in the Latin horologmm and in the French horloge. Following the

example of Athens, the other Hellenic cities coveted the honor of

possessing sun-dials, and their astronomers proved equal to the task of

applying the principle to the position of each. The apparent path of the

sun varied of course with the latitude of each place, and the length of

the shadow cast by the stylus It was consequently different in one city

and another. At Alexandria it was only three-fifths of the height of the

stylus, at Athens three-quarters; it was nearly nine-elevenths at Tarentum

and reached eight-ninths at Rome. As many different sun-dials had to be

constructed as there were different cities. The Romans were among the last

to appreciate the need. And just as they felt no need to count the hours

till two centuries after the Athenians, so they took another hundred years

to learn to do it accurately.

|

At the end of the fourth century B.C. they were still content to divide the day

into two parts, before midday and after. Naturally the important thing was then

to note the moment when the sun crossed the meridian. One of the consul's

subordinates was told off to keep a lookout for it and to announce it to the

people busy in the Forum, as well as to the lawyers who, if their pleadings were

to be valid, must present themselves before the tribunal before midday. The

herald's instructions were to make his announcement when he saw the sun "between

the rostra and the graecostasis (a place in

the Forum)"

By the time of the wars against Pyrrhus some slight progress had been made by

dividing the two halves of the day into two parts: into the early morning and

forenoon on one hand; and afternoon and

evening on the other. But it was not until the beginning of the First Punic War in

264 B.C. that the "hours" and horologium (sun-dial, see

sidebar) of the Greeks were introduced

into the city. One If the consuls of that year, Valerius Messalla, had

brought back with other booty from Sicily the sun-dial of Catana and set it up as

it was on the comitium (an assembly

place), where for more than three generations the lines

engraved on its face for another latitude continued to supply the Romans with an

artificial time. In spite of the assertion of Pliny the Elder that they blindly

obeyed it for ninety-nine years, we must think that

they persisted in ignorance rather than in willful error. They probably took no

interest at all in Messalla's sun-dial and continued to govern their day in the

old happy-go-lucky manner by the apparent course of the sun above the monuments

of their public places, as if the horologium had never existed.

In the year 164 B.C., however, three

years after Pydna, the enlightened generosity of the censor Q. Marcius Philippus

endowed the Romans with their first horologium accurately calculated for their

own latitude and hence reasonably accurate, and if we are to believe Pliny the

Naturalist, they welcomed the gift as a coveted treasure. For thirty years their

legions had fought in Greek territory, almost without ceasing, first against

Philip V, then against the Aetolians and Antiochus of Syria, finally against

Perseus; and they had gradually become familiar with the possessions of their

enemies. At times, perhaps, they had toyed, without undue success, with a system

of hours a trifle less erratic and uncertain than the one that had hitherto

sufficed them. So they were pleased to have a sun-dial brought home and fitted

up in their own country. Not to be behind Q. Marcius Philippus, the censors who

succeeded him in office, P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica I and- M. Popilius Laenas,

completed the work he had begun by flanking his sun-dial with a water-clock to

supplement its services at night or on foggy days.

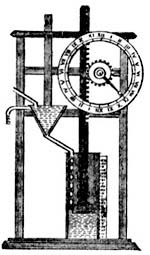

Roman Water Clocks

It was more than a hundred years since the Alexandrians had equipped

themselves with water-clocks

which Ctesibius had

evolved from the ancient water-clocks to remedy the inevitable failure of the

horologium proper. This became known in Latin as the horologium ex aqua.

Nothing could well have been simpler than the mechanism of the water-clock.

Let us imagine the water-clock- that is, a transparent vessel of water

with a regular intake- placed near a sun-dial. When the gnomon casts its

shadow on a curve of the vessel, we need only to mark the level of the

water at that moment by incising a line on the outside of the water container.

When the shadow reaches the next curve of the polos, we make another

mark, and so on until the twelve levels registered correspond to the twelve

hours of the day chosen for our experiment. This being granted, it is

clear that if we give our clepsydra a cylindrical form we can engrave on

it from January to December twelve vertical lines corresponding to the twelve

months of the year. On each of these verticals we then mark the twelve hourly

levels registered for the same day of each month; and finally, by joining with a

curved line the hour signs which punctuate the monthly verticals, we can read

off at once from the level of the water above the line of the current month the

hour which the needle of the sun-dial would have registered at that moment-if

the sun had happened to be shining. which Ctesibius had

evolved from the ancient water-clocks to remedy the inevitable failure of the

horologium proper. This became known in Latin as the horologium ex aqua.

Nothing could well have been simpler than the mechanism of the water-clock.

Let us imagine the water-clock- that is, a transparent vessel of water

with a regular intake- placed near a sun-dial. When the gnomon casts its

shadow on a curve of the vessel, we need only to mark the level of the

water at that moment by incising a line on the outside of the water container.

When the shadow reaches the next curve of the polos, we make another

mark, and so on until the twelve levels registered correspond to the twelve

hours of the day chosen for our experiment. This being granted, it is

clear that if we give our clepsydra a cylindrical form we can engrave on

it from January to December twelve vertical lines corresponding to the twelve

months of the year. On each of these verticals we then mark the twelve hourly

levels registered for the same day of each month; and finally, by joining with a

curved line the hour signs which punctuate the monthly verticals, we can read

off at once from the level of the water above the line of the current month the

hour which the needle of the sun-dial would have registered at that moment-if

the sun had happened to be shining.

Once the sun-dial had lent its services for grading the water- clock, there was

no further need to have recourse to the dial, and it was a simple matter to

extend the readings to serve for the night hours. It is easy to imagine that the

use of clepsydrae soon became general in Rome. The principle of the

sun-dial was still sometimes applied on a grandiose scale: in 10 B.C., for

instance, Augustus erected in the Campus Martius the great obelisk of

Montecitorio to serve as the giant gnomon whose shadow would mark the daylight

hours on lines of bronze inlaid into the marble pavement below. Sometimes, on

the other hand, it was applied to more and more minute devices which eventually

evolved into miniature solaria or pocket dials that served the same purpose

as our watches. Pocket sun-dials have been discovered at Forbach and Aquileia

which scarcely exceed three centimeters in diameter. But at the same time the

public buildings of the city and even the private houses of the wealthy were

tending to be equipped with more and more highly perfected water-clocks. From

the time of Augustus, clepsydrarii and organarii rivaled each

other in ingenuity of construction and elaboration of accessories. As our clocks

have their striking apparatus and our public clocks their peal of bells, the

horologia ex aqua which Vitruvius describes were fitted with automatic

floats which "struck the hour" by tossing pebbles or eggs into the air or by

emitting warning whistles.

The

fashion in such things grew and spread during the second century of our era. In

the time of Trajan a water-clock was as much a visible symbol of its owner's

distinction and social status as a piano is for certain strata of our middle

classes today. In Petronius' romance, which represents Trimalchio as "a highly

fashionable person" , his confederates frankly justified the admiration

they felt for him: "Has he not got a clock in his dining-room? And a uniformed

trumpeter to keep telling him how much of his life is lost and gone?" Trimalchio,

moreover, has stipulated in his will that his heirs shall build him a sumptuous

tomb, with a frontage of one hundred feet and a depth of two hundred, "and

let there be a sun-dial in the middle! so that anyone who looks at the time will

read my name whether he likes it or not." This quaint appeal to posterity would

have no point if Trimalchio's contemporaries had not been accustomed frequently

to consult their clocks. It is clear that the hourly division of the day had

become part and parcel of their everyday routine. On the other hand, it would be

an error to suppose that the Romans lived with their eyes glued to the needles

of their sun-dials or the floats of their water-clocks as ours are to the hands

of our watches. They were not yet like us the slaves of time, for they still

lacked both perseverance and punctuality. The

fashion in such things grew and spread during the second century of our era. In

the time of Trajan a water-clock was as much a visible symbol of its owner's

distinction and social status as a piano is for certain strata of our middle

classes today. In Petronius' romance, which represents Trimalchio as "a highly

fashionable person" , his confederates frankly justified the admiration

they felt for him: "Has he not got a clock in his dining-room? And a uniformed

trumpeter to keep telling him how much of his life is lost and gone?" Trimalchio,

moreover, has stipulated in his will that his heirs shall build him a sumptuous

tomb, with a frontage of one hundred feet and a depth of two hundred, "and

let there be a sun-dial in the middle! so that anyone who looks at the time will

read my name whether he likes it or not." This quaint appeal to posterity would

have no point if Trimalchio's contemporaries had not been accustomed frequently

to consult their clocks. It is clear that the hourly division of the day had

become part and parcel of their everyday routine. On the other hand, it would be

an error to suppose that the Romans lived with their eyes glued to the needles

of their sun-dials or the floats of their water-clocks as ours are to the hands

of our watches. They were not yet like us the slaves of time, for they still

lacked both perseverance and punctuality.

In the first place, we may be very sure that the agreement between the sun-dial

and the water-clock was still far from being exact. The gnomon of the sun-dial

was correct only in the degree in which its maker had adapted it to the latitude

of the place it where it stood; and as for the water-clock, whose measurements

lumped all the days of one month together though the sun would have lighted each

differently, its makers could never prevent certain inaccuracies in its floats

creeping in to falsify the corrections they had been able to make in the

readings of the gnomon. If anyone asked the time, he was certain to receive

several different answers at once for, as Seneca asserts, it was impossible at

Rome to be sure of the exact hour; and it was easier to get the philosophers to

agree among themselves than the clocks. Time at Rome was never more than

approximate.

Time was perpetually fluid or, if the

expression is preferred, contradictory. The hours were originally calculated for

daytime; and even when the water-clock made it possible to calculate the night

hours by a simple reversal of the data which the sun-dial had furnished, it did

not succeed in unifying them. The horologia ex aqua was built to reset

itself, that is, to empty itself afresh for night and day. Hence a first

discrepancy between the civil day, whose twenty-four hours reckoned from

midnight to midnight, and the twenty-four hours of the natural day which was

officially divided into two groups of twelve hours each, twelve of the day and

twelve of the night!

Nor was this all. While

our hours each comprise a uniform sixty minutes of sixty seconds each, and each

hour is definitely separated from the succeeding by the fugitive moment at which

it strikes, the lack of division inside the Roman hour meant that each of them

stretched over the whole interval of time between the preceding hour and the

hour which followed; and this hour interval instead of being of fixed duration

was perpetually elastic, now longer, now shorter, from one end of the year to

the other, and on any given day the duration of the day hours was opposed to the

length of the night hours. For the twelve hours of the day were necessarily

divided by the gnomon between the rising and the setting of the sun, while the

hours of the night were conversely divided between sunset and sunrise; in

proportion as the day hours were longer at one season, the night hours were, of

course, shorter, and vice versa. The day hours and night hours were equal only

twice a year: at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. They lengthened and

shortened in inverse ratio till the summer and winter solstices, when the

discrepancy between them reached its maximum. At the winter solstice (December

22), when the day had only 8 hours, 54 minutes of sunlight against a night of 15 hours, 6 minutes, the day hour shrank to 44 minutes while in compensation

the night hour lengthened to 1 hour, 15 minutes. At the summer solstice the

position was exactly reversed; the night hour shrank to its minimum while the

day hour reached its maximum. Nor was this all. While

our hours each comprise a uniform sixty minutes of sixty seconds each, and each

hour is definitely separated from the succeeding by the fugitive moment at which

it strikes, the lack of division inside the Roman hour meant that each of them

stretched over the whole interval of time between the preceding hour and the

hour which followed; and this hour interval instead of being of fixed duration

was perpetually elastic, now longer, now shorter, from one end of the year to

the other, and on any given day the duration of the day hours was opposed to the

length of the night hours. For the twelve hours of the day were necessarily

divided by the gnomon between the rising and the setting of the sun, while the

hours of the night were conversely divided between sunset and sunrise; in

proportion as the day hours were longer at one season, the night hours were, of

course, shorter, and vice versa. The day hours and night hours were equal only

twice a year: at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. They lengthened and

shortened in inverse ratio till the summer and winter solstices, when the

discrepancy between them reached its maximum. At the winter solstice (December

22), when the day had only 8 hours, 54 minutes of sunlight against a night of 15 hours, 6 minutes, the day hour shrank to 44 minutes while in compensation

the night hour lengthened to 1 hour, 15 minutes. At the summer solstice the

position was exactly reversed; the night hour shrank to its minimum while the

day hour reached its maximum.

Thus at

the winter solstice the day hours were as follows:

| I. Hora

prima from 7:33 to 8:17 A.M. |

VII. septima 12:00 to 12:44 P.M.

|

| II. secunda 8:17 to 9:02

|

VIII. octava 12:44 to 1.29 |

| III. tertia 9:02 to 9:46

|

IX. nona 1:29 to 2:13

|

| IV. quarta 9:46 to 10:31

|

X. decima 2:13 to 2:58

|

| V. quinta 10:31 to 11:15

|

XI. undecima 2:58 to 3:42 |

| VI. sexta 11:15 to 12.00 noon.

|

XII. duodecima 3:42 to 4:27 P.M. |

The night hours naturally reproduced in rigorous antithesis the equivalent

fluctuations, with their maximum length at the winter solstice and their minimum

at the summer solstice.

These

simple facts had a profound influence on Roman life. For one thing, as the means

of measuring the inconstant hours remained inadequate and empirical throughout

antiquity, Roman life was never regulated with the mathematical precision which

The above schedule, drawn up

according to our methods, might suggest, and which tyrannizes over the

employment of our time. Busy as life was in the city, it continued to have

elasticity unknown to any modern capital. For another thing, as the length of

the Roman day was indefinitely modified by the diversity of the seasons, life

went through phases whose intensity varied with the dimensions of the daily

hour, weaker in the somber months, stronger when the fine and luminous days

returned; which is another way of saying that even in the great swarming city,

life remained rural in style and in pace.

Based on Daily

Life in Ancient Rome by Jerome Carcopino

History of Time Keeping

ClockWatch Home Page

| | |